Impacts of the McKenna McBride Commission

By 1924, eight years after the McKenna McBride Commission concluded, the Federal and Provincial governments had placed themselves in a position to approve and adopt the Royal Commission Report. After the lengthy review and negotiation process undertaken by W. E. Ditchburn and Col. J. W. Clark [see Background narrative for details], both governments agreed upon policies that asserted colonial control over land and ignored Aboriginal Title and Rights. The effects of not negotiating Aboriginal Title and Rights and the impacts of the governments' decisions and policies continue to be felt strongly by First Nations in British Columbia today.

The implementation of the Royal Commission Report furthered the assertion of colonial authority over First Nations in British Columbia. This assertion was made through new legislation and regulations.

For example:

- the Federal/Provincial governments gave themselves authority to cut-off land from existing reserves without consultation or consent of First Nations

- restrictions were placed on the mobility of First Nations on and off the reserves

- resistance to colonial authority was made almost completely illegal

These obstacles did not, however, stop First Nations from continuing their struggle to have Aboriginal Title and Rights recognized by the Federal and Provincial governments.

Legislative and Legal Impacts of the Royal Commission

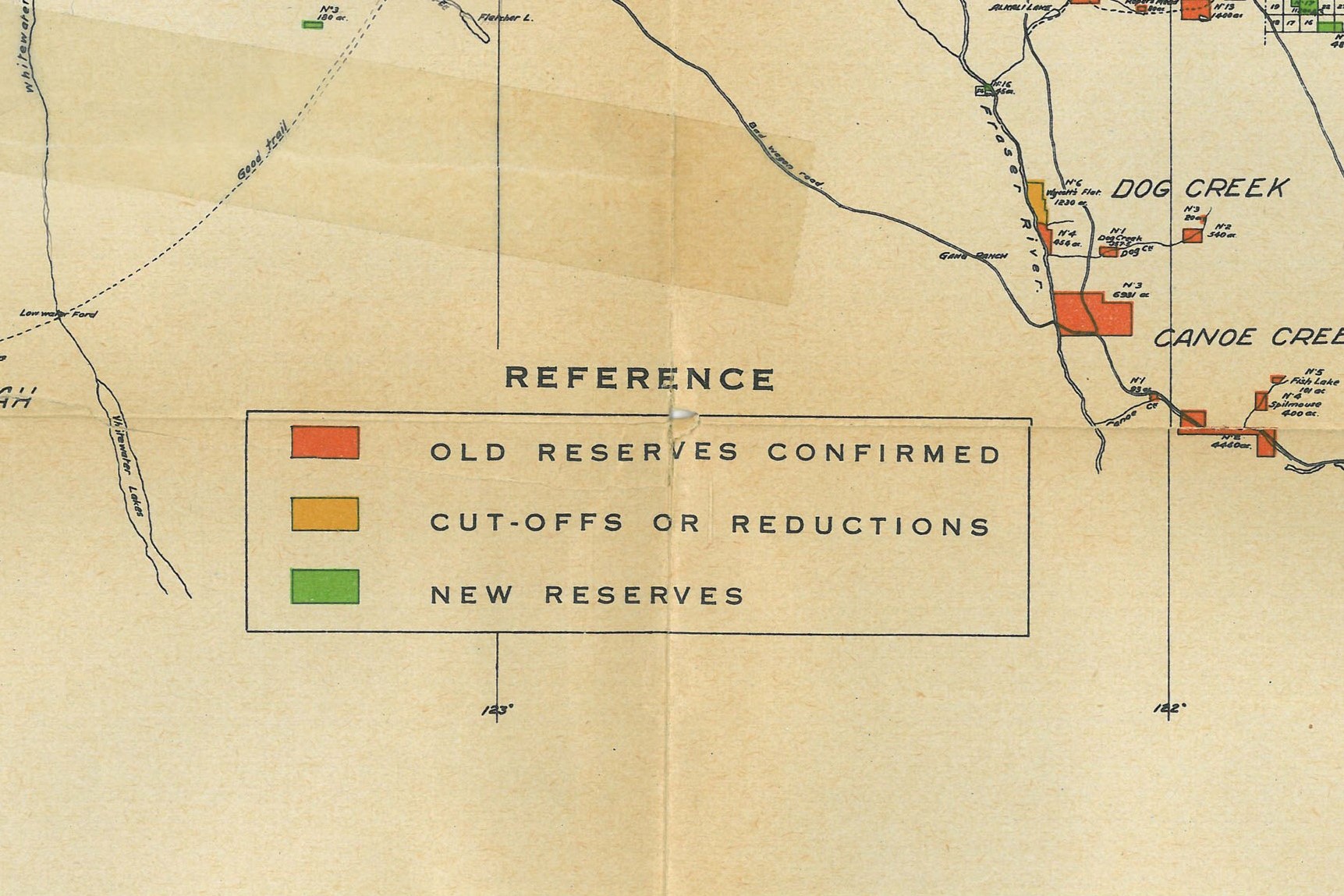

As outlined by the Commissioners themselves, consent had to be given by the majority of adult male Band members before the government could make any changes to the physical layout of the reserves. Because consent was not received, the Federal and Provincial governments agreed to pass two pieces of legislation to give themselves permission to ignore this requirement. The Federal government passed their law first in 1919, entitling it The Indian Affairs Settlement Act. The Province of British Columbia followed in 1920 with the Land Settlement Act. After passing these acts, the governments cut off over 36,000 acres of land from reserves all over British Columbia without consultation, consent, or compensation.

Organized opposition and umbrella organizations already active for many years prior to the Commission, such as the Indian Rights Association and the Interior Tribes of British Columbia, fought against the government in the struggle to protect Aboriginal Title and Rights. Resistance specific to the McKenna McBride Royal Commission emerged immediately following the creation of the Commission in 1913.

In 1916, the Allied Indian Tribes was formed out of a conference held by prominent First Nations activists, Andrew Paull and Peter Kelly. The goal of the Allied Tribes was to seek a resolution to land claims in British Columbia through negotiation with the Federal and Provincial governments. On behalf of the Aboriginal Peoples of British Columbia, the Allied Tribes lobbied relentlessly against the adoption of the cut-offs recommended in the Report of the Royal Commission. The Allied Tribes also produced a detailed rejection (Statement of the Allied Tribes) of the report. It consisted of nine reasons for refusal to accept, including:

- the Commission's failure to deal with, or even recognize, Aboriginal Title and Rights

- the Commissioners had failed to address the inequalities between tribes with respect to both area and value of previous reserve allotments

- the Commissioners had failed to make adjustments to water rights

The recommendations of the Royal Commission were eventually adopted in 1924 without First Nations' consent and without adequate amendments addressing the concerns expressed by the Allied Tribes and other activists. The investigation of the Royal Commission and the advocacy of Indian rights pursued by the Allied Tribes and other political organizations and activists contributed to the long and successful history of political activism among First Nations in British Columbia.

Further Opposition to the Commission

One of the foremost non-Indigenous advocates working on behalf of the Indians in British Columbia and alongside the Allied Tribes was A. E. O'Meara. A controversial character, he provided legal advice to the Indians during their ongoing dialogue with the Federal and Provincial governments from the beginning of the Royal Commission through to the carrying out of its recommendations. O'Meara was a founding member of the Society of Friends of the Indians of British Columbia which raised money for Indian political activity and sponsored public talks on issues related to the Indian land question. While this activism was well-intentioned, it has been argued that it was fixed in a paternalistic framework. The Federal government, also thinking that First Nations activism required non-Indigenous guidance, assumed that after O'Meara's death, agitation would simply fade away.

In response to the growing opposition from the First Nations organizations, the Federal government revised the Indian Act in 1927 to further limit Indian actions. Section 141 of the revised Indian Act prohibited Indians from raising money, hiring lawyers, and pursuing land claims. At the same time, the Federal government strengthened existing prohibitions against the potlatch.

Section 140 stated that Indians found participating in potlatches could be sent to prison for up to six months. The wording of Section 140 was so broad that it could have been applied to almost any gathering organized by Indians. The potlatch ban negatively impacted many features of First Nations culture, and also directly affected the freedom of First Nations people to meet, discuss, and pursue the advancement of such issues as Aboriginal Title and Rights; A third limit on First Nations' freedom to meet and organize was the restriction placed on travel off reserve. In order to leave the reserve, they first had to request permission from the Indian Agent. The Indian Agent had complete power to reject or accept requests, making it difficult for Bands to organize across reserves. All of these laws were protected and upheld by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (R.C.M.P.).

Loss of Land

First Nations people suffered devastating impacts as the result of the loss of their land and all the natural resources that flowed from the land. With the reduction in reserve size and lack of mobility on surrounding lands, Indian access to land and resources became restricted to the reserve boundaries. For example, in areas of the province where First Nations people were traditionally dependent on salmon, some adjustments made by the Royal Commission either reduced, restricted or eliminated Native access to salmon. The adjustments made to the reserves allowed settlers to fish further downstream, giving them access to the salmon before First Nations. At the same time, salmon spawning areas were being destroyed due to neighbouring resource development such as mining.

The ability to remain self-sufficient declined, which led to the creation of a social system where First Nations became dependent on the government.

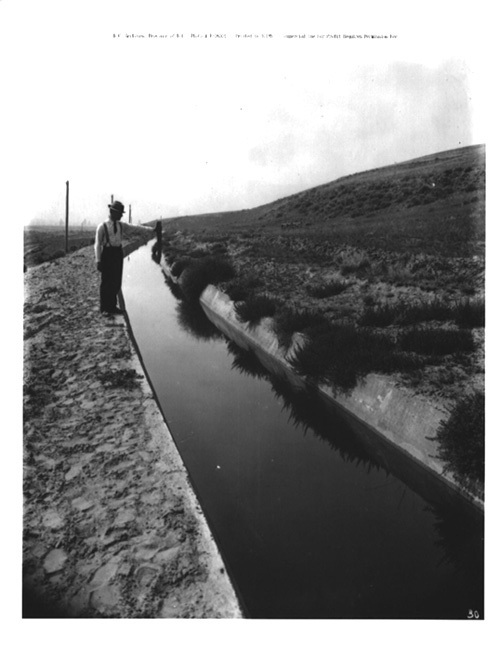

Testimonies (click here to search the testimonies) from the Royal Commission hearings indicate that the Federal and Provincial governments, along with Indian Agents, actively encouraged First Nations to abandon traditional practices in favour of European agricultural and cultivation practices. First Nations people were encouraged to cultivate their reserve lands despite lacking the resources to do so successfully. Lands not being used for European style farming, were considered inadequately used or completely unused. Even people who wanted to farm on reserves faced difficulties, as seen in the testimonies at the Royal Commission. For example:

- reserve lands were often of poor quality for farming

- they had insufficient access to water for irrigation

- First Nations people lacked the financial resources needed (farm equipment, seed, etc.) in order to farm effectively

Impacts on First Nations Culture

Between the loss of land and the colonial governments asserting their authority, First Nations' social and economic networks that had been upheld for generations began to fall apart. First Nations culture, being so deeply rooted in a connection to the land, could not but be affected by land changes resulting from the Royal Commission. In essence, cutting First Nations access to land was cutting away their culture.

The laws discouraging First Nations from organizing also had a destructive impact on the culture of communities. Participation in potlatches, for which jail time was being enforced, was integral to First Nations societies and economies and ensured prosperity for all Band members. This, along with other factors such as Indian children being taken from their homes and placed in residential schools, disease, and substance abuse, took a toll on the cultural unity of First Nations communities.

Development of the Claims Processes

Despite the laws that attempted to squash First Nations resistance to the colonial powers, Indian political organization continued to thrive. Andy Paull, Peter Kelly and others fought against the prohibitions against potlatching and fundraising. In 1951 these sections of the Indian Act were dropped. First Nations struggles to have the McKenna McBride cut-off lands returned to their reserves and for the recognition of Aboriginal Title and Rights were no longer illegal.

Returning Cut-off Lands

In 1967 the Squamish Band initiated a claim that began the development of a formal McKenna McBride cut-off claim process. Anxious to have their grievances recognized and settled, the Squamish Band and several other First Nations began negotiations with the Federal and Provincial governments. Unsuccessful negotiation led eight Nations to file lawsuits in 1979 against the federal government seeking return of, or compensation for, the cut-off lands. The claim of the Penticton Band was eventually the first settlement to be negotiated. The Penticton settlement was then used as a template for other cut-off claims. In 1996 the revised Indian Cut-Off Lands Dispute Act was created to deal exclusively with unresolved McKenna McBride cut-off claims in British Columbia.

Aboriginal Rights and Title : Specific Claims Policy

In 1973 the Federal government developed the Specific Claims policy that was later published as Outstanding Business: A Native Claims Policy in 1982. Specific Claims were limited to claims about the Federal administration of land. The policy was intended to eliminate some barriers to negotiating cut-off claims and settlements; it was not an apology or an admission of legal liability. According to Specific Claims in Canada Status Report, 1985, final settlements had been reached with 82 to 84 Bands. The McKenna McBride grievances had been important in the shaping of the Specific Claims process, however, since the legislation of 1996, unresolved McKenna McBride claims are considered apart from the Specific Claims process.

Comprehensive Claims

A Federal Comprehensive Claims policy initiating the Comprehensive Claims process was implemented in 1973. The Comprehensive Claims policy was supposed to address Aboriginal people's traditional jurisdiction over land and resources. From the Federal government's standpoint, Comprehensive Claims showed the government's willingness to listen to First Nations' grievances about issues of Aboriginal Title and Rights by negotiating claims based on traditional use and occupancy.

The Provincial government of British Columbia was not initially part of Comprehensive claims discussions. Although British Columbia entered negotiations with the development of the British Columbia Treaty Commission in 1992, the province was not willing to recognize Aboriginal Title until after 1997. The province's approach to Aboriginal Title changed after the 1997 Delgamuuk'w decision.

An ongoing point of contention in the Comprehensive Claims process is that the Federal and Provincial government will only come to the negotiating tables if Aboriginal communities are willing to extinguish their land Title in treaties. The general response from the Aboriginal communities has been that extinguishments of Title is not an option - that this formula for treaty negotiation would destroy the goals of co-existence by eliminating Aboriginal sovereignty and culture.

While there is general agreement amongst First Nations to protect Aboriginal sovereignty and culture, communities have chosen to deal with the situation in different ways. Some Nations have been willing to enter into negotiations with the government in good faith, while others refuse. In the past eighty years, since the end of the McKenna McBride Commission, trust has yet to be established between First Nations and the Federal/Provincial governments.

Summary

The full impact of the Royal Commission on First Nations people remains unknown, as the restrictions to land use continue to impact First Nations culture, identity, health and welfare almost one century later. Time, resources, and effort spent fighting human rights injustices committed by the colonial government, has taken away from the re-building of Aboriginal communities. Despite ongoing hardships, First Nations cultures survive and the people continue to fight against the injustices of the colonial legacy.